Discipline is the impossible conquered by the obstinate repetition of the possible.

From A philosophy of walking by Frédéric Gros. 📚

Discipline is the impossible conquered by the obstinate repetition of the possible.

From A philosophy of walking by Frédéric Gros. 📚

Human dignity must be associated with the idea of a scamp and not with that of an obedient, disciplined, and regimented soldier…. In the present age of threats to democracy and individual liberty, probably only the scamp and the the spirit of the scamp alone will save us from becoming lost as serially numbered units in the masses of disciplined, obedient, regimented and uniformed [removed pejorative]. The scamp will be the last and most formidable enemy of dictatorships. He will be the champion of human dignity and individual freedom, and will be the last to be conquered. All modern civilization depends entirely upon him.

From The Importance of Living by Lin Yutang 📚

Human personality is the last thing to be reduced to mechanical laws; somehow the human mind is forever elusive, uncatchable and unpredictable, and manages to wriggle out of mechanistic laws or a materialistic dialectic that crazy psychologists and unmarried economists are trying to impose upon him. Man, therefore, is a curious, dreamy, humorous and wayward creature.

From The Importance of Living by Lin Yutang 📚

[Ishiguro] is a planner, patient and meticulous. Before he begins the writing proper, he will spend years in a sort of open-ended conversation with himself, jotting down ideas about tone, setting, point of view, motivation, the ins and outs of the world he is trying to build.

Only once he has drawn up detailed blueprints for the entire novel does he set about the business of composing actual sentences and paragraphs. In this, too, he follows a set of carefully honed procedures.

First, writing very quickly and without pausing to make revisions, he’ll draft a chapter in longhand. He then reads it through, dividing the text into numbered sections. On a new sheet of paper he now produces a sort of map of what he has just written, summarizing in short bullet points each of the numbered sections from the draft.

The idea is to understand what the different sections are doing, how they relate to one another and whether they require adjustment or elaboration. Working from this sheet, he then produces a flow chart, which in turn serves as the basis for a second, more painstaking and deliberate draft. When this is finished to his satisfaction he finally types it up. Then he moves on to the next chapter and the process starts again.

From Kazuo Ishiguro Sees What the Future Is Doing to Us, The New York Times Magazine. 📚

Other than explicitly not living his dream, is Kazuo Ishiguro living the dream? In his own words, from a recent NYT Magazine feature:

In some ways, I suppose, I’m just not that dedicated to my vocation. I expect it’s because writing wasn’t my first choice of profession. It’s almost something I fell back on because I couldn’t make it as a singer-songwriter. It’s not something I’ve wanted to do every minute of my life. It’s what I was permitted to do. So, you know, I do it when I really want to do it, but otherwise I don’t.

📚

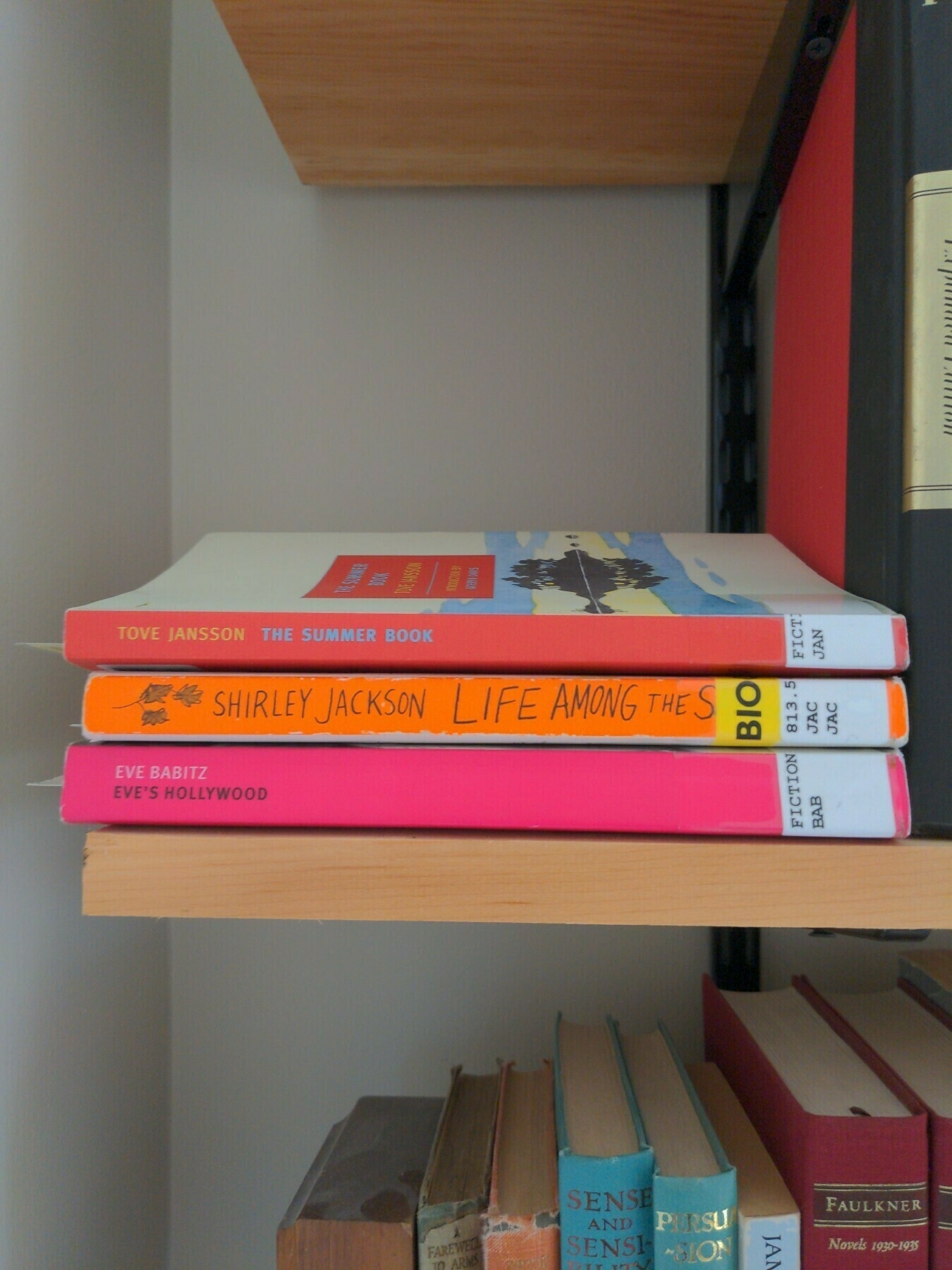

Currently reading

[Kant] was awoken each morning at five o’clock, never later. He breakfasted on a couple of bowls of tea, then smoked a pipe, the only one of the day. On teaching days, he would go out in the morning to give his lecture, then resume his dressing-gown and slippers to work and write until precisely a quarter to one. At that point he would dress again to receive, with enjoyment, a small group of friends to discuss science, philosophy, and the weather.

There were invariably three dishes and some cheese, placed on the table - sometimes with a few desserts - along with a small carafe of wine for each guest. Conversation lasted until five o’clock.

Then it was time for his walk. Rain or shine, it had to be taken. He went alone, for he wanted to breath through his noe all the way, with his mouth closed, which he believed to be excellent for the body… He always took the same route, so consistently that his itinerary through the park later came to be called ‘The Philosopher’s Walk’.

From A philosophy of walking by Frédéric Gros. 📚

The urban stroller is subversive. The walker of wide-open spaces, the trekker with his rucksack opposes civilization with the burst of a clean break, the cutting edge of a rejection. The stroller’s walking activity is more ambiguous, his resistance to modernity ambivalent. Subversion is not a matter of opposing by evading, deflecting, altering with exaggeration, accepting blandly and moving rapidly on. The flâneur subverts solitude, speed, dubious business politics and consumerism.

From A philosophy of walking by Frédéric Gros. 📚

Our judgement of an established author is never simply an aesthetic judgment. In addition to any literary merit it may have, a new book by him has a historic interest for us as the act of a person in whom we have long been interested. He is not only a poet or a novelist; he is also a character in our biography.

From The Dyer’s Hand by W.H. Auden 📚

Between the ages of twenty and forty we are engaged in the process of discovering who we are, which involves learning the difference between accidental limitations which it is our duty to outgrow and the necessary limitations of our nature beyond which we cannot trespass with impunity.

When someone between twenty and forty says, apropos of a work of art, ‘I know what I like,‘he is really saying ‘I have no taste of my own but accept the taste of my cultural milieu’, because, between twenty and forty, the surest sign that a man has a genuine taste of his own is that he is uncertain of it.

From The Dyer’s Hand by W.H. Auden 📚

Walking is the best way to go more slowly than any other method that has every been found. To walk, you need to start with two legs. The rest is optional. If you want to go faster, then don’t walk, do something else.

From A philosophy of walking by Frédéric Gros. 📚

Craig Mod’s recent essay on looking closely reminded me of Houellebecq reading Schopenhauer, and in particular the centrality of careful observation/representation to the artistic process:

Before Schopenhauer, the artist was generally seen as someone who manufactured things… But the original point, the generating point of all creation… consists in an innate (and thus not teachable) disposition for passive and, as it were, dumbstruck contemplation of the world…

A work of art, in Schopenhauer’s conception, is a kind of product of nature; it must share with nature a simplicity of purpose, an innocence…

Once I read this I had to re-read The Map and the Territory. I think, when I first read this novel, that it seemed likely the character Jed was Houellebecq’s send-up of the art world, the author having vicious fun at the expense of the character (probably a safe baseline assumption reading Houellebecq).

That seems wrong now. Jed is an artist in the full, unironic Schopenhauerian sense:

Today, when art has become accessible to the masses and generates considerable financial flows, this has very comical consequences. Thus, the ambitious and enterprising individual with a range of social skills who nurses the ambition to have a career in art will rarely succeed; the palm will always go to the pathetic blob-like folk who everyone initially thought were just losers…

Since the idea is and remains intuitive, the artist is not aware in abstract terms of the intention and purpose of his work.

📚

My library recently added a “borrowing history” page (belated, but welcome. Thanks TPL!). Suitably enabled, I decided to make myself a books I’ve read / skimmed / started page! 📚

Just finished That old country music by Kevin Barry, highly recommended. Recently finished Drive your plow over the bones of the dead by Olga Tokarczuk and To begin where I am : selected essays by Czesław Miłosz. 📚