Custom word search

I haven’t done specific New Years Resolutions in a few years, but for 2024 I have three:

Ready to go!

Updated my reading page this morning!

In the car this morning, my four year old said “Dad, can you play the Robert Henry song?” #winning

Spalted maple bud vase

Driftwood burl

Go Leafs Go. Buds in 6.

First bowl of the spring. Pretty pleased with this little guy.

We have a teenager on our block - maybe 18 or 19 years old - who for the last two years could be regularly seen zipping around the place on his E-bike.

We called him E-bike Kid.

Now he has a (somewhat noisy) car… and when we hear it go by, we still say “there goes E-bike Kid.”

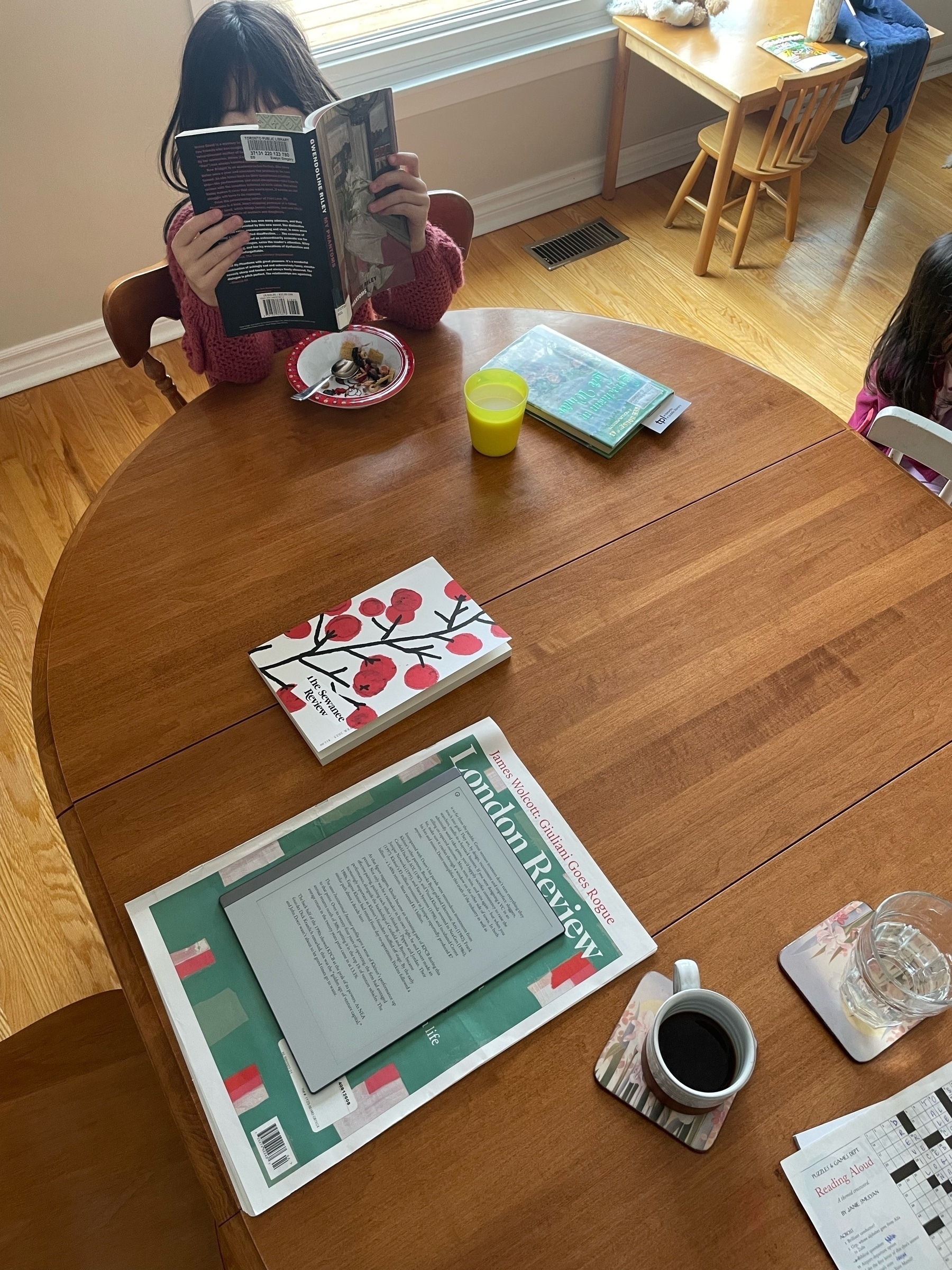

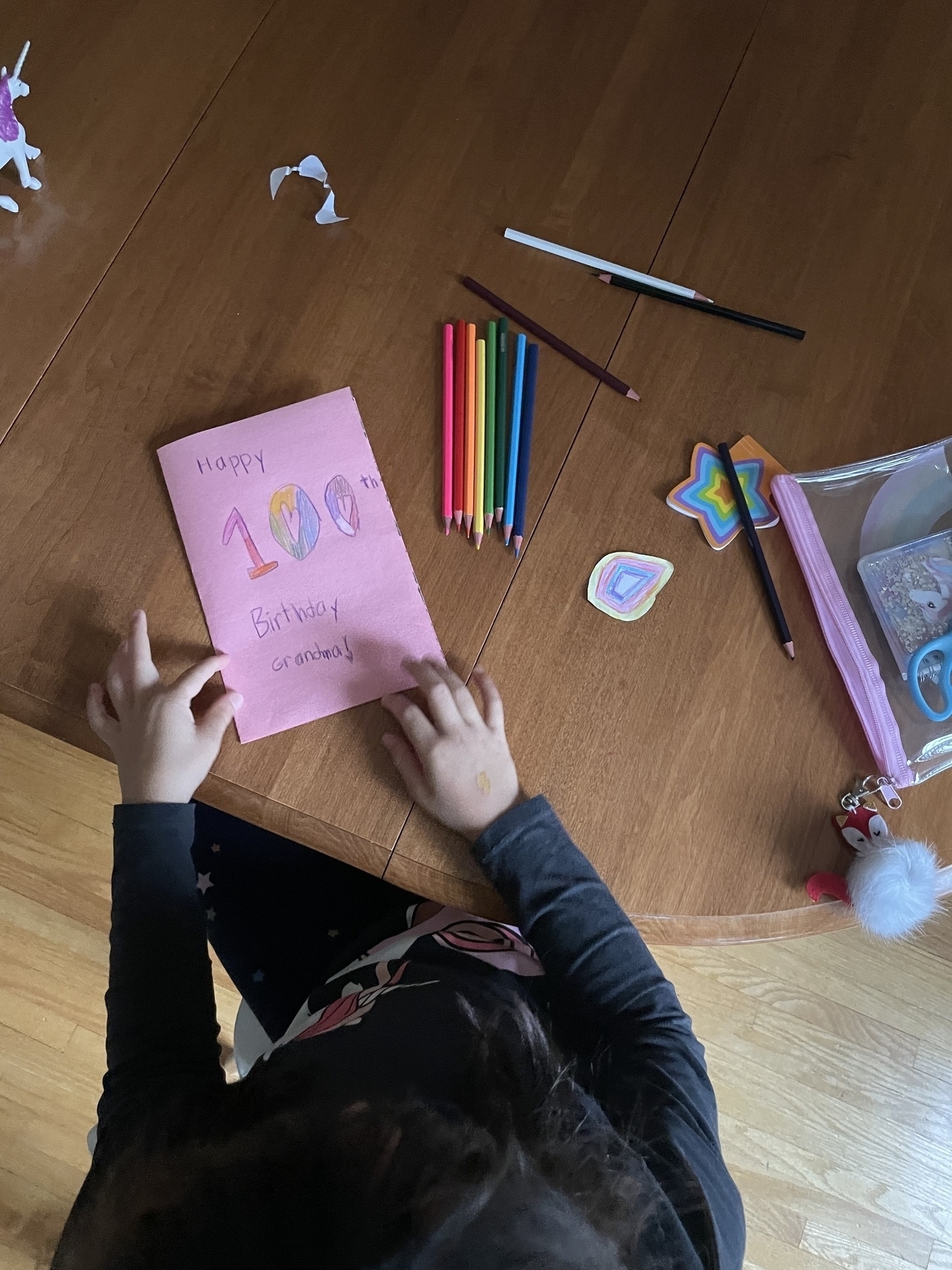

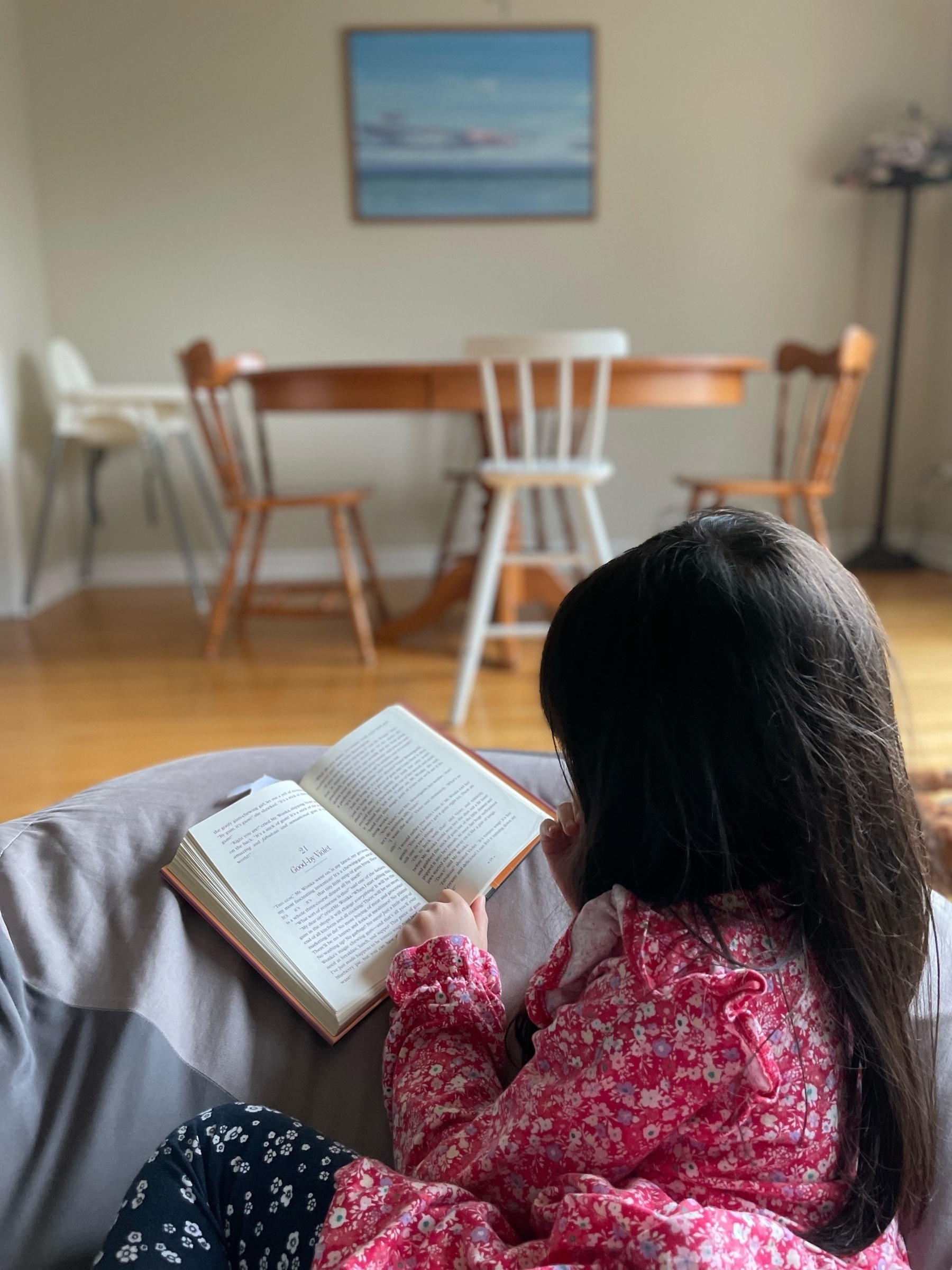

A perfect Saturday morning