Skeptical 📷

Skeptical 📷

Yahtzee! 📷

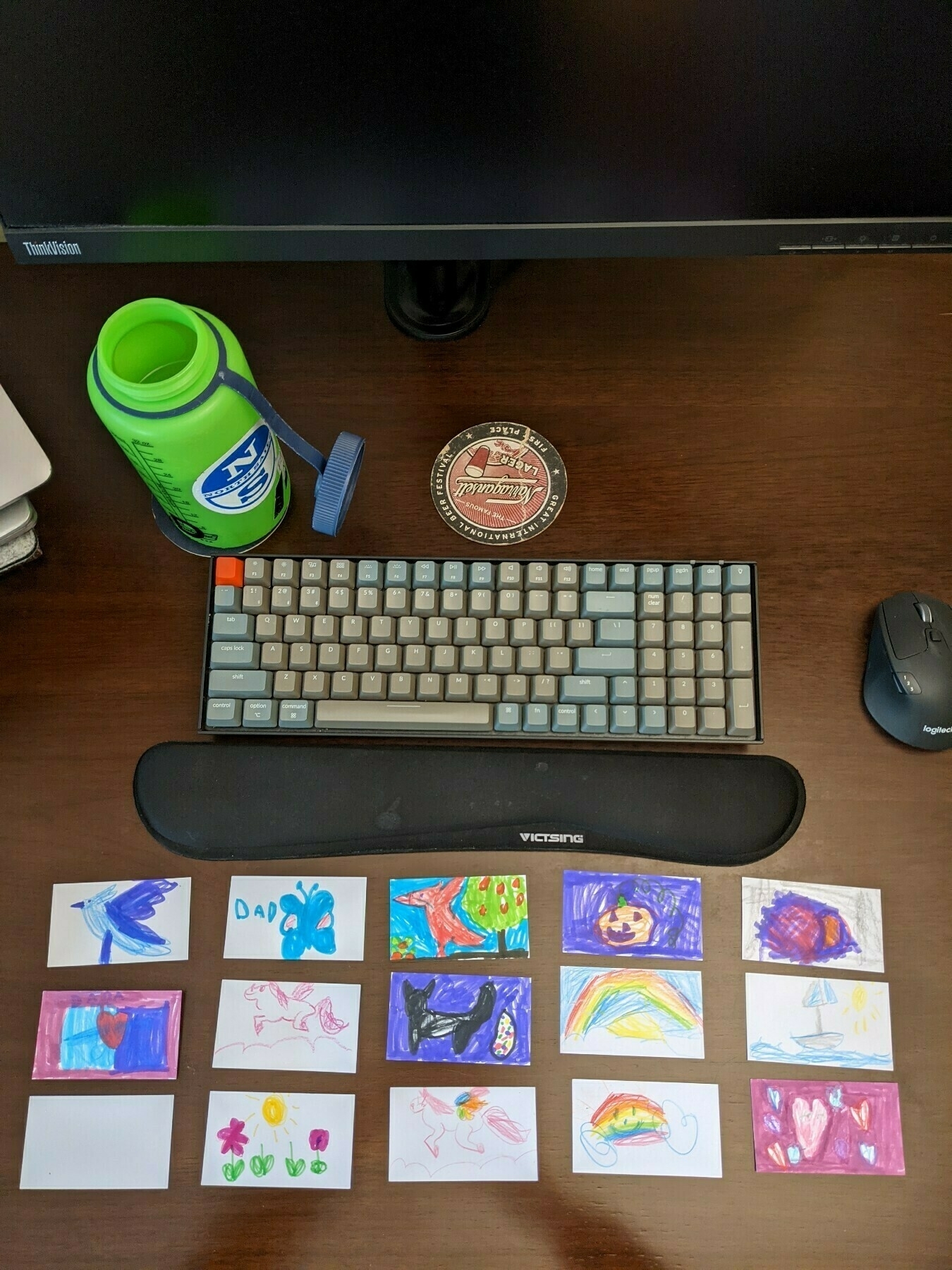

New business cards 📷

[Oakeshott] admires those who, whether humble or exalted, poor or rich, ordinary or brilliant, in different ways achieve a sense of themselves and a style that shows their success in achieving individual humanity. There are no collective achievements in these matters. We are to each other not role models but additions to the variety of human possibilities to be enjoyed.

From Timothy Fuller’s foreword to Rationalism in politics and other essays 📚.

📷

📷

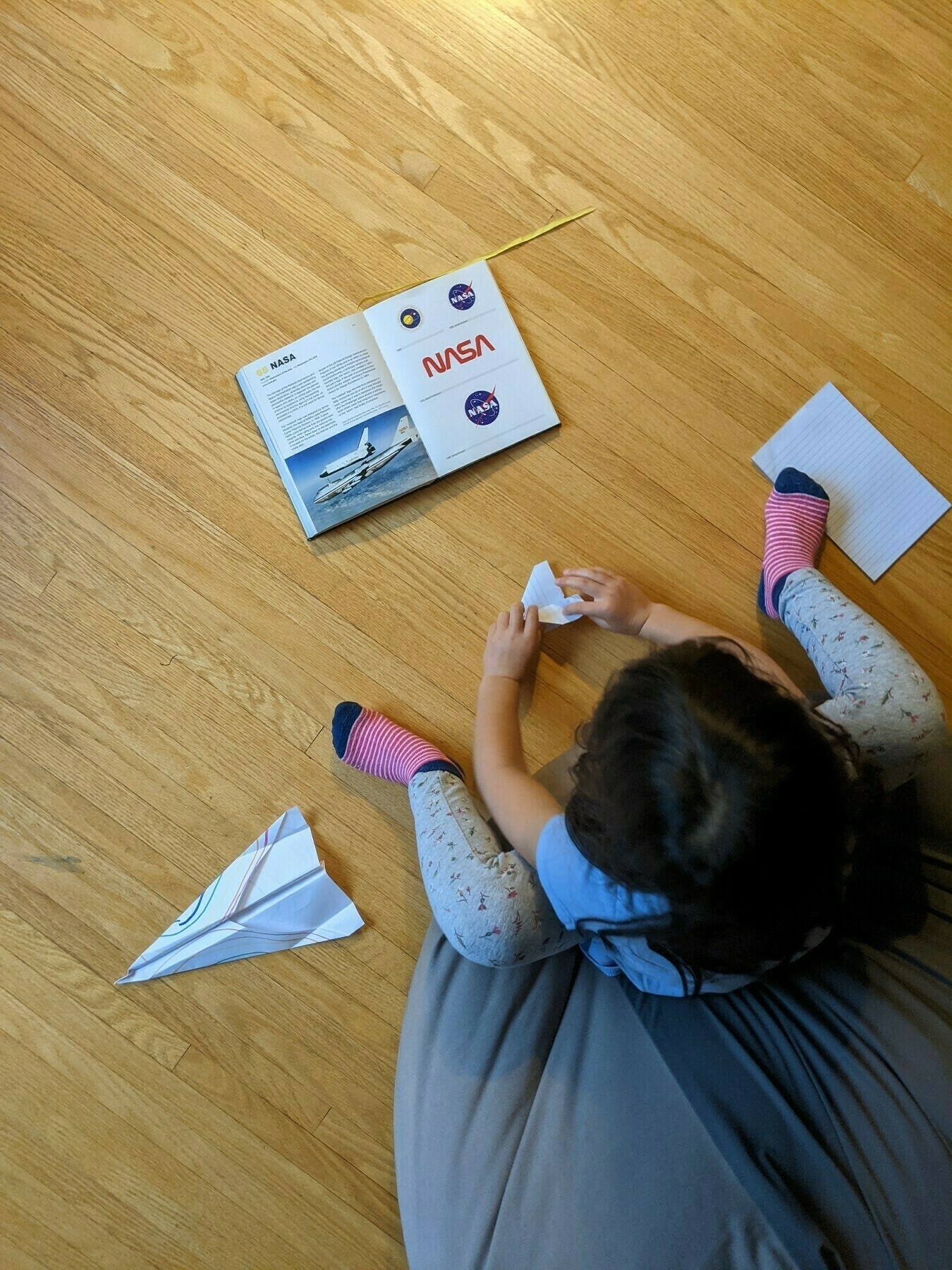

A paper Discovery morning 📷 🚀🧑🚀

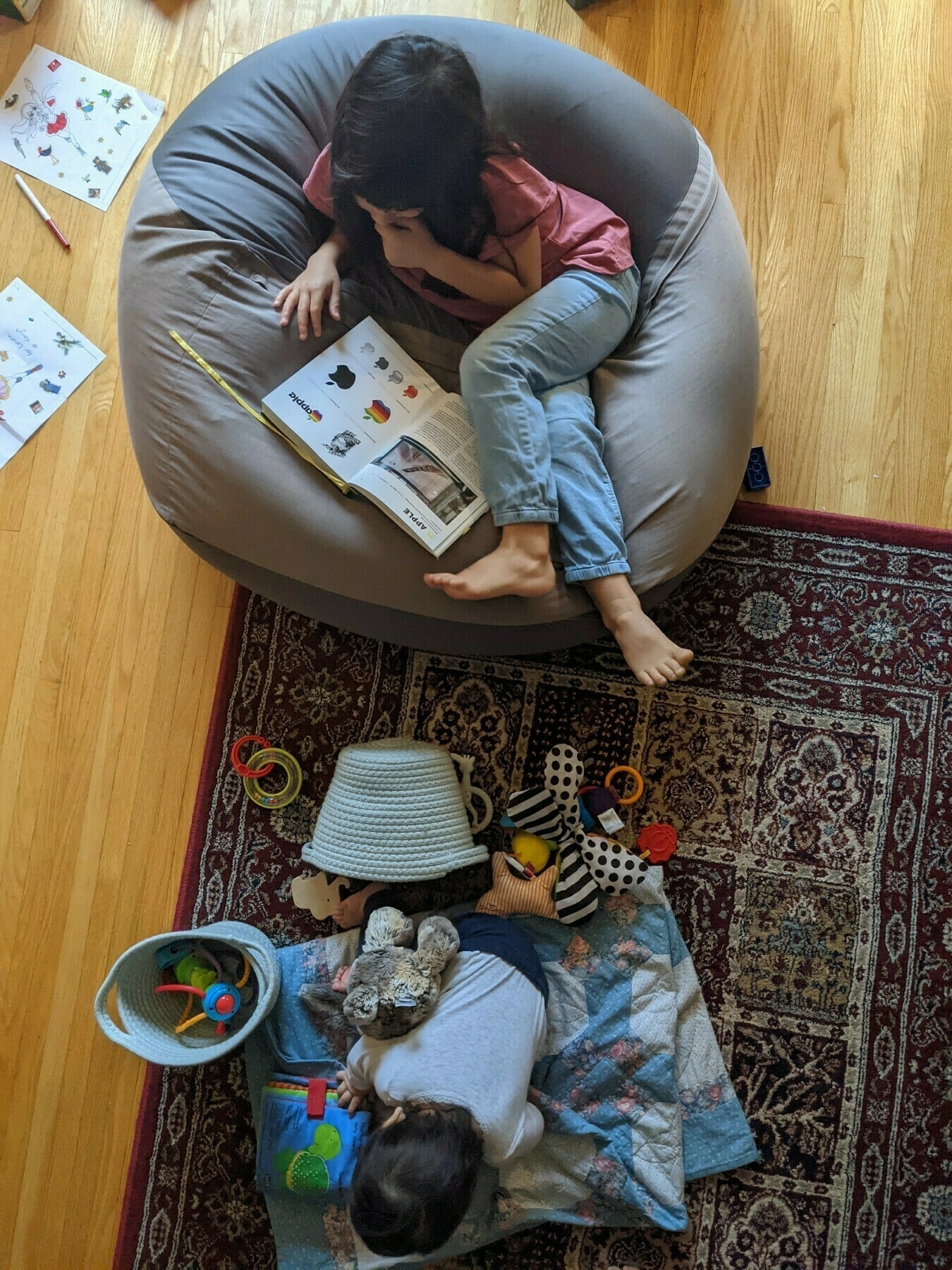

Lounging with logos 📷 🍏

Back in her childhood she used to have holy feelings, knifelike flashes that laid the earth open like a blue watermelon, when the sun came down to her like an elevator she was sure she could step inside and be lifted up, up, past all bad luck, past every skipped thirteenth floor in every building human beings had ever built. She would have these holy days and walk home from school and think, After this I will be able to be nice to my mother, but she never ever was, After this I will be able to talk about only what matters, life and death and what comes after, but still she went on about the weather.

From Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This 📚

Sunday morning walk 🌂

I have finished Beautiful World, Where Are You and in my dream I was wrong: the balance Rooney’s characters navigate isn’t between fragility and fun, but rather joy (and beauty, and truth). But I wasn’t off by too much! 📚

I started reading Sally Rooney’s new novel Beautiful World, Where Are You last night 📚. I made it just under half way through.

This isn’t an original thought: Rooney is exceptionally talented. She has an “easy virtuosity” and dialogue, especially, shimmers off the page. It helps that the gift of the gab is an Irish thing, and in my mind she just absolutely nails the voices she is working to create. I find, when reading Rooney, I think to myself “I should try to be a writer”. She makes it look easy.

Who am I quoting up above, you may be wondering? The answer is myself, in a dream I had last night.

I dreamt that I was sitting in a university lecture hall listening to an honourary lecture given by a professor I had several classes with when I was in undergrad, Julian Patrick. Unsurprisingly Professor Patrick’s lecture was focused on the Rooney’s novel.

He made the case that Beautiful World, Where Are You concerns and is concerned with fragility. Rooney’s characters recognize but cannot escape the pressure the world puts on them, large and small. Their fragility within this context is notable, Prof. Patrick argued, and provide an interpretive lens through which we can make one sense at least of the text.

And then, after kind of wandering over in my direction (I was sitting in the front row) Prof. Patrick leaned in towards me and whispered, “Got anything else?”

So in the dream I thought for a moment, cleared my throat, and started talking. I distinctly remember the feeling of uncertainty and surprise that the rest of the audience expressed at that moment: we were less than five minutes into the lecture, and it was unusual for an audience member to being speaking at this point without any indication that we had moved into Q&A or a more conversational mode for the session.

And here’s what I said, more or less, as far as I can remember it: It is true that there is a strong element of fragility in how Rooney constructs her characters. They think about their position within a fraught and unjust social order; they struggle under the expectations placed on them by family, friends, the market, themselves; they navigate intimacy with uncertainty, sensitive to the different ways that interpretation could change the fundamentals of how a particular interaction with another might be understood. They struggle with sadness, feelings of inadequacy, being overwhelmed, moments of hypocrisy, and constant major or minor assaults to their mental health broadly speaking.

But balanced against this fragility is something else, I said (in my dream, to an audience that was now listening carefully): fun. They have and are fun, in many respects! They have deep friendships with each other. There is lots of playful banter. They are young and enjoying themselves, at least some of the time. Certainly the sex is often good, both for the characters involved and in the way Rooney writes it. The main characters seem to be living with some degree of authenticity to their own vision of their lives (however fraught that ends up being). They express their views confidently and seem to enjoy the back and forth this creates with the people around them.

The point isn’t that fragility isn’t important; rather, that Rooney balances that fragility with indications of another way of living, a fun and lively way of interacting with the world. The novel, I argued in my dream to my dream audience, is less about either side and more about the balance or between the two. And that balancing between paired elements is reproduced throughout the text. Friendship and romance; success and failure; faith and rationality; familial bonds and gulfs. The letters (emails?) exchanged between Alice and Eileen throughout are the perfect vehicle for expressing this: at once social, written for another, audience in mind, and at the same time deeply interior, reflective and crafted with and through introspection.

Granted, I’m only half way through (I was only half way through in my dream as well). But what emerges is the sense of making do, of navigating through extremes with some level of grace, relying on those around us to the extent we are able, finding meaning as honestly as we can, being sensitive to difference and to inconsistency but also to patterns and structure in how we are with others. I’m not sure this made it into my impromptu lecture, but in my mind (or the mind of my dreaming, lecturing self, which I am struggling to separate from what I actually think about the text) Rooney rejects both a pessimistic acceptance of fragility as the defining feature of how we live now, but also isn’t staking out a position that what we need to cultivate is antifragility in Taleb’s sense. There’s some path between the two.

It was an interesting dream. I’m interested to see whether my dream take on the novel holds up as I continue reading.

An every 10 year birthday present (more or less) 🎂

Saturday morning 🌞 📷

For about twenty-five years I have been copying sentences into the back pages of whatever notebook I happen to be using, using mostly for other purposes…. Of course there are sentences elsewhere in these books: even the briefest, most telegraphic, verbless note is a sentence of sorts. But the end-of-notebook sentences are different, even if someone them come from books I’m reviewing and so on. Unconnected to duty or deadlines, to projects per se, they compose a parallel timeline — of what?

I suppose the word is: affinity.

From the first chapter of Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence, describing a practice that I’m emulating, to some extent, here on this blog. Again, closer to the end of the chapter:

So, not a treasury, then — something closer, I hope, to a kind of commonplace book, product of haphazard notation, ad hoc noticing.

Leylah 🇨🇦 vs Emma 🇬🇧 is, for me, a can’t lose match. I’m excited for both of them and delighted regardless of outcome. It’s a rare and awesome feeling!! 🎾

The September 6 issue of The New Yorker has re-prints of two phenomenal pieces by Zadie Smith (from 2013) and Anthony Bourdain (from 2000). Highly recommended! 📚

I’m excited about my library holds list. Should be an excellent autumn for reading :)

Remote work mostly destroys the ability to appear busy, other than having a full calendar. Being on lots of calls does not actually have an output if you’re just on them to waffle on about some bullshit, and bosses no longer have the mechanism to appear busy other than doing work.

From The Work-From-Home Future Is Destroying Bosses' Brains published on Ed Zitron’s Substack. 📚

A picture of a video of a puffin 📷

Morning reading 📷 📚

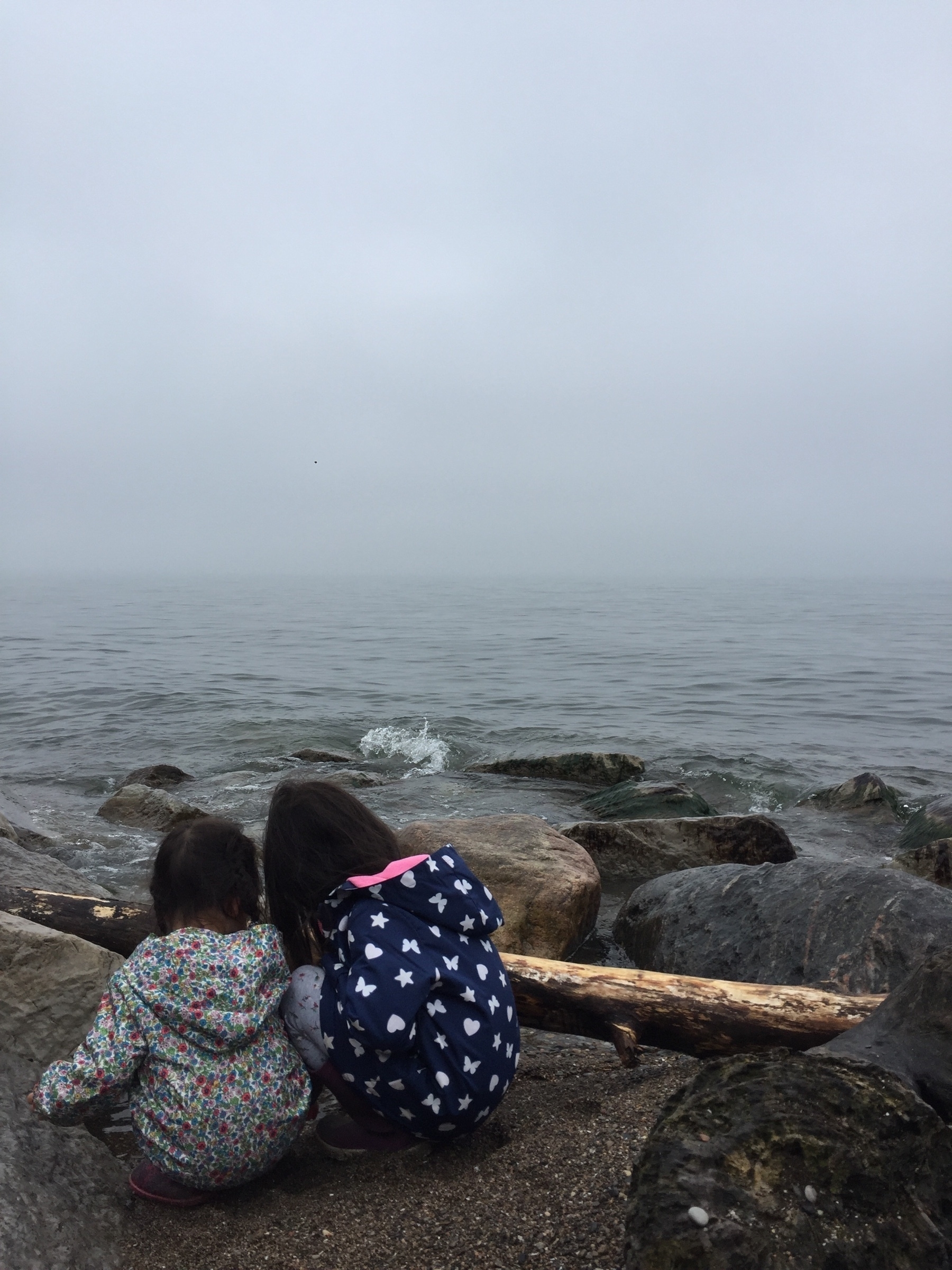

Lookout 📷 🏖️

[Mona] remembered something she’d heard a while back from her friend Vlad, a sixty-something Russian novelist she’d met at Iowa during a prestigious writers' residency in the middle of Yankee Nowhere, at a time when Mona was still a newcomer to the circuit. According to Vlad… peace reigned in Iowa “only beacause we don’t understand each other’s languages, and our ignorance protects us.” To illustrate his point, Vlad told Mona he’d participated in residencies that included composers and musicians as well as writers — and that was real hell. Peace between musicians, Vlad continued, was impossible, because they could all tell who was a real genius and who was just a mediocre poseur. Music was a transparent field in which genius and mediocrity were self-evident truths — and this only ever led to hatred, distrust, and malaise. No doubt about it: not knowing each other’s languages was the key to conviviality, because if we were able to read what everyone else was writing, if we were able to understand it and feel it like music, the Russian calmly concluded, well, then we’d be murdering each other in our beds.

From Mona by Pola Oloixarac 📚