Updated my reading page this morning!

Historical detective work

In 1933, at the age of eighteen, Patrick Leigh Fermor began to walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople. Years later his notes and reflections became two book length treatments of the trip: A Time of Gifts and Between the Wood and the Water (joined posthumously by an unfinished draft of the last portion of the journey, The Broken Road). These have been favourites of mine for a long time, and I recently decided to re-read them.

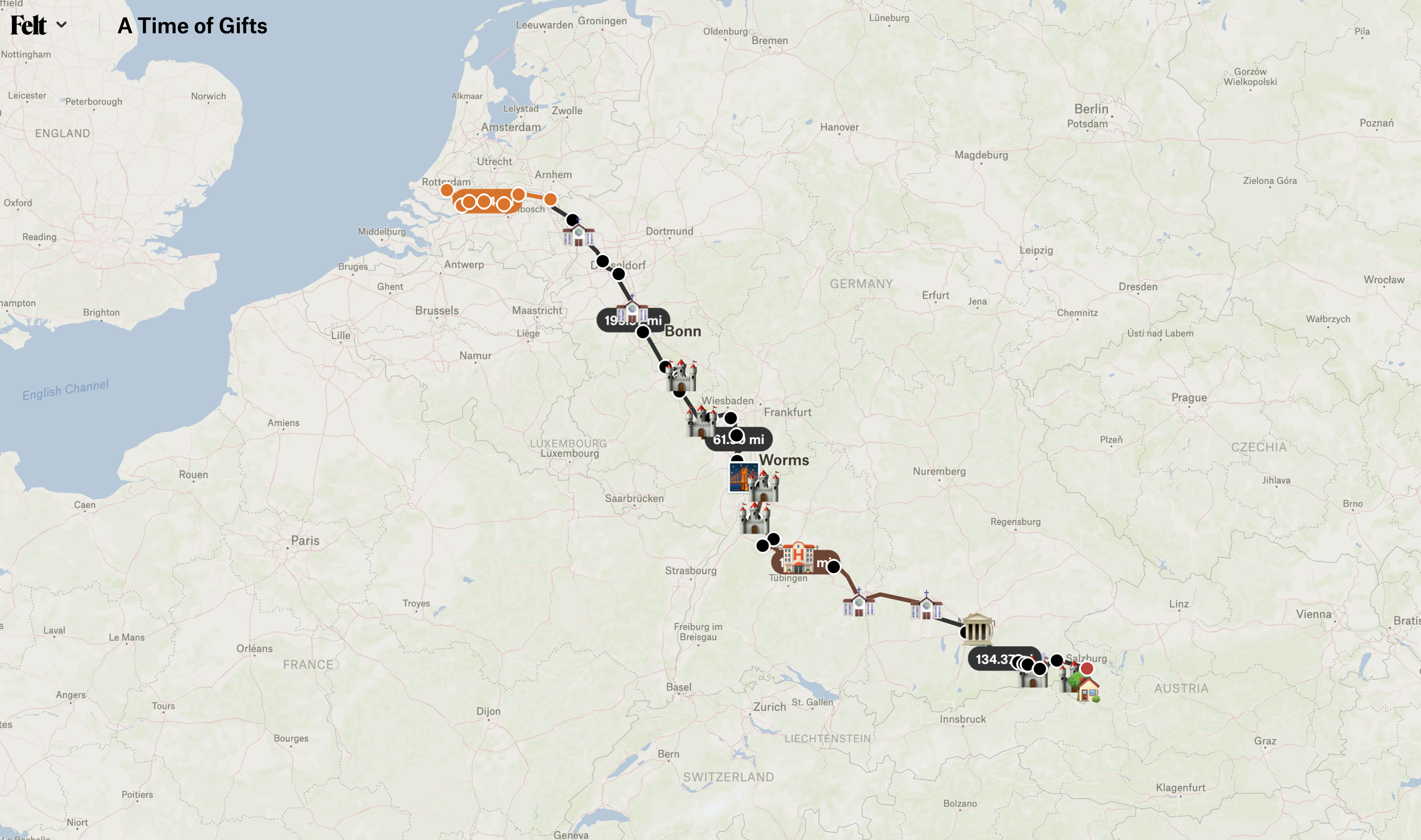

One day I hope to repeat portions of Fermor’s walk in person; this time, I decided to follow along virtually. While I didn’t start with a plan, I quickly settled on a straightforward approach: I read each chapter with a pen and notebook handy, recording place names and key details as they appeared in the narrative. Once a chapter was complete, I took my notes to the computer. Initially I began looking place names up on Google Maps and saving the results as a starred location. Google Maps isn’t ideal for this, though, and so I switched to a new product, Felt. “the best way to make maps on the internet.” I figured this was a pretty good use case.

The result has been a map that develops as I read. I’m not taking advantage all of Felt’s features, but the basic ones are quite useful. I can look up and mark locations on the map, distinguishing by pin type where it makes sense (I’ve been marking castles and churches in particular). I can trace a walking route between pins; I’m not trying to mirror the specific route Fermor took – In many places, that might be impossible even if it was well documented – but it is nice to think that the route is snapping to a walking route, even if it probably isn’t the exact one Fermor used.

I’m not sure how surprising this should be, but the exercise has been exceptionally satisfying. Taking notes while reading has made me a more active, engaged participant in the story; tracing locations on a map has made the journey real in a way that I previously haven’t had access to (I don’t have any personal experience with walking Central Europe)! It helps, of course, that the map is a rich one. Fermor is able to name an amazing number of villages, towns, abbeys, cathedrals, and castles. In sequence, they come together into a realized, highly plausible reconstruction of the journey.

The exceptions are, in many cases, by design. Fermor is welcomed into the homes and histories of many titled families along his journey. These parts of the story are some of the most interesting, but Fermor is understandably reticent about the particulars of many of these visits.

As far as reconstructing the route goes, however, this discretion will not do. And in places, Fermor includes so many potentially identifying details he is practically inviting a little bit of sleuthing, a little bit of work on the part of the reader to fill in these particulars he, with some discretion, has left out. I was happy to leave these parts of the trip fuzzy on previous reads, but this time around I am invested in accuracy! And so where we have some details of a visit or a stop, but no explicit identifying information, I’ve felt compelled to spend at least a little bit of time tracking down a hint of the particulars.

Here’s one example of this.

Chapter 6 of A Time of Gifts finds the young Fermor walking through Austria in the mid-winter of 1934, just about to turn nineteen. Working his way north of Salzburg, Fermor follows the path of the Danube. An earlier encounter with a German Baron in Ulm had opened doors into other great houses along the route. Fermor comes within reach of the first of these soon after visiting Gottweig Abbey, Austria’s Monte Cassino. Based on the understanding that he was more or less expected, he puts in a call; his hosts, despite not actually having any advance warning – the letter from the Baron would arrive a day after Fermor – welcome him in. But neither these hosts, nor the schloss itself, are ever mentioned by name.

Fermor drops a number of tantalizing clues while narrating his brief visit, however. Here’s what we know:

- The castle is an easy half day’s walk from Gottingen Abbey. It has a proper moat and battlements.

- His host is known as Graf (Count) Joseph, and is one of two brothers who live in the house. The lady of the house is of Greek extraction

- The family has a famous ancestor who’s portrait hangs in a main room: a major figure in the Thirty Year’s War and the Peace of Westphalia, he is described as having a Don Juan beard, a gold chain around his neck, wearing all black, and having a “smart and ugly” countenance.

- At the end of the visit, Fermor is chauffeured to a rural train station nearby on the St. Polten - Vienna line.

With these details in play, Fermor is basically begging his readers to do a bit of detective work. So I obliged.

My starting point was the information available about the castle itself. A quick google search reveals six castles within seven hours of Gottweig: Atzenbrugg, Wurmla, Viehoven, Totzenbach, Wasserburg, and Pottenbrunn. Of these, the first three aren’t equipped with moats, so we can exclude them from any further look. Google Maps says that the walk between Gottweig and Totzenbach should take around six and a half hours, which to me is a little more than an “easy half day’s walk”. The walk to Wasserburg and Pottenbrunn are around 4 hours: very reasonable. I decided to focus in on these two castles for further analysis.

I started with Schloss Wasserburg. It doesn’t look particularly castle-ly, but it does have moat. One of the top Google Search results is a Spotting History write up of the castle, which indicates that Count Carl Hugo Seilern von Aspang bought the property in 1923, 10 years before Fermor passed through. The fact that the owner at the time was Count seemed promising! A little more googling brought me to a Geni page for Count Carl Hugo, which reveals that one of his middle names was Joseph, he had at least one brother, and his wife was born in Romania. Romania isn’t Greece, but it isn’t entirely off base either. Was Fermor a guest at Schloss Wasserburg at the invitation of the Seilern von Aspangs? I decided to look into Schloss Pottenbrunn before deciding… but absent any new information, I was ready to say I had figured it out.

Schloss Pottenbrunn looks a lot more like a true castle than Wasserburg. It has a proper moat and is located close to the St. Polten line. Wikipedia tells us that it was acquired by the Trauttmansdorff family in 1926. Almanach de Saxe Gotha gives us a lot more information about this particular family: apparently some of them are princes and princesses, but cadet members are Count or Countesses von und zu Trauttmansdorff-Weinsberg. Further down the page we find Carl Joseph, one of the only Trauttmansdorffs who is plausibly the right age to host Fermor (he was born in Vienna in 1897, and died in 1976). A separate google search turns up Carl Joseph’s Geneanet page: he had a male sibling, Ferdinand, and a Czech (not Greek) wife named Johanna.

So far, so good: the castle fits (moat and all), and Carl Joseph and Johanna seem to be plausible hosts. The final piece to confirm: did they have a famous ancestor? I googled “trauttmansdorff westphalia thirty years war” and the first result is a Britannica page for Maximilian: “confidant of the emperors Ferdinand II and Ferdinand III, chief imperial plenipotentiary during the negotiations of the Peace of Westphalia, and one of the foremost political figures of early 17th-century Europe.” We’ve got our guy. Because Fermor mentions the portrait, I also did a quick google search, and it turns out the young traveller captured all the key details of the most famous portrait of the man, right down to his, smart, ugly countenance.

Our sleuthing done, we can fill one of the only significant gaps in Chapter 6: it’s extremely likely that Fermor’s last stop before Vienna was with Carl Joseph and Johanna at Schloss Pottenbrunn.

I’m re-reading Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts; this time I’m building a map of his journey as I go on Felt 📚 🗺

There was nothing show-offy about friendships then. Your friends were simply who was around. It didn’t occur to anyone that it could be another way. If you liked your friends, that was okay. If you didn’t like your friends, that was okay, too. We were fine living our mediocre lives. It didn’t occur to anyone that we could have great ones.

From Sheila Heti’s Pure Colour 📚.

Considering one’s life requires a horribly delicate determination, doesn’t it? To get to the truth, to the heart of the trouble. You wake and your dreams disband, in a mid-brain void. At the sink, in the street, other shadows crowd in: dim thugs (they are everywhere) who’d like you never to work anything out.

From Gwendoline Riley’s First Love 📚.

Despite knowing little or nothing of the bloody, mucky realities of land-based lives, people sometimes tell me to be careful not to romanticise the past. On this, I agree. But I tell them to be even more careful of romanticising the future.

From Mark Boyle’s The Way Home 📚.

It has ever been a hindrance to some and a blessing to others that the inbred egoism of the human race blinkers even the perceptive nature. The world revolves, we can agree. But secretly each believes that it revolves around them. Knowing this is a help to the salesperson and the diplomat, but no comfort to the distressed creature who convinces themselves that the machinery of the universe has uniquely conspired to obturate them in the hunt for happiness.

From James Greer’s Bad Eminence 📚.

To gaze upon a childhood home through adult eyes is an act of disenchantment. Great doors grow small. Turrets vanish. Emblems fray. Even if the time spent within any given set of walls was, when the days are reckoned together, brief, it’s in the nature of childhood to guild all surfaces it touches, to magnify things. One should revisit such places only after having done some hard calculations: What are we willing to trade for a clear view of things? What are the chances we’ll regret the bargain later on?

From John Darnielle’s Devil House 📚.

Any of us can do something good, in writing, when the world gives us a shove, but a true writer is inevitable only when we recognize in the work a unique and unmistakable universe of words, figures, conflicts.

But I tend to imagine, first, that the ordinary person and the extraordinary person set off from the same terrain: literary writing with its cathedrals, its country parishes, its tabernacles in dark territories; and, second, that chance plays the same role in both the minor work and the great work.

Elena Ferrante, writing in Harper’s 📚

As you surface from an hour inadvertently frittered away… you’d be forgiven for assuming that the damage, in terms of wasted time, was limited to that single misspent hour.

But you’d be wrong.

Because the attention economy is designed to prioritize whatever’s most compelling — instead of what’s most true, or most useful — it systematically distorts the picture of the world we carry in our heads at all times. It influences our sense of what matters, what kinds of threats we face, how real our political opponents are, and thousands of other things — and all these distorted judgements then influence how we allocate our offline time as well…

So it’s not simply that our devices distract us from more important matters. It’s that they change how we’re defining “important matters” in the first place.

From Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks 📚. If this is true (and I think it is) then its effects are proportional to the degree to which an individual (or community) in question is “very online”. Blue-check journalism Twitter springs very much to mind here.

This story by Lauren Groff is my favourite thing I’ve read in a while. 📚

From the kitchen, the smell of bread lifts, smooth white rolls speaking careful English for the family, brown loaves laughing in Irish for everyone else.

From Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat 📚

Stars have always done asset-based wealth building, just like any other rich person, but quietly—celebrities who buy up rental properties or fast-food franchises generally have not sought public praise for becoming landlords, or for extracting wealth from the labor of the working poor.

Now everyone from Justin Bieber to Shaq wants to be treated as a cultural visionary for placing six-digit bets on the long-term value of a digital receipt for an ugly cartoon, and they want you to know this is the new cool thing, and there’s still time for you to get in on the ground floor.

If Hilton and Fallon and their celebrity friends are going to go out there and pump-and-dump their way to additional wealth, they could at least do the rest of us the courtesy of being a little more discreet about it.

📚 Finished Trust by Domenico Starnone. I was struck by two things: first, the success with which Starnone renders Pietro both insecure and assured; second, the way he builds around the central conceit (a shared, shameful secret) so successfully he ends up not relying on it at all.

People in uniform had always bothered me and when I drank I felt an absolute necessity to tell them that. I picked on anyone in uniform, even streetcar drivers, but apart from police officers my favorites were hotel doormen.

From Gianfranco Calligarich’s Last Summer in the CIty 📚

I got out of bed four days later and, sneezing fiercely, caught a bus and went and recovered my old Alfa Romeo, feeling as if it was a part of me that had blown off in an explosion. On the way back, I stopped to buy more aspirin and a few provisions, then shut myself in at home, determined not to go out until the world had apologized to me.

It did its best, truth be told. The days were warm and the sky a disarming blue, but in a way the very beauty of the weather merely increased my anguish.

From Gianfranco Calligarich’s Last Summer in the CIty 📚

I’ve been doing some prep reading over the last few weeks to get ready for a new job. Some of these are close reads, some of these are more for skimming, but I’ve gotten something valuable out of all of them.

Intro to Venture Capital

- Secrets of Sand Hill Road: Venture Capital — and How to Get It by Scott Kupor (2019)

- Venture Capitalists at Work: How VCs Identify and Build Billion-Dollar Successes by Tarang Shah with Shital Shah (2011)

- Mastering the VC Game by Jeffrey Bussgang (2010)

Refreshing Scrum / Agile Knowledge Base

- Fixing Your Scrum: Practical Solutions to Common Scrum Problems by Ryan Ripley and Todd Miller (2020)

- Essential Scrum: A Practical Guide to the Most Popular Agile Process by Ken Rubin (2011)

- Agile Product Management with Scrum by Roman Pichler (2009)

Startups and Entrepreneurship

- The Cold Start Problem: How to Start and Scale Network Effects by Andrew Chen (2021)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy Answers by Ben Horowitz (2014)

- Startup Boards: Getting the Most Out of Your Board of Directors by Brad Feld and Mahendra Ramsinghani (2013)

- The Lean Startup by Eric Ries (2010)

- The Four Steps to the Epiphany: Successful Strategies for Products that Win by Steven Blank (2006)

Thinking about DevOps / MLOps +

- MLOps: Continuous Delivery for Machine Learning on AWS (2020)

- MLOps: Continuous delivery and automation pipelines in machine learning (2020)

- Amazon Machine Learning Developer Guide (2021)

- MLOps is a Practice, Not a Tool by JL Marechaux (2021)

- What you need to know about product management for AI (2020)

- People + AI Guidebook (2021)

- Continuous Delivery for Machine Learning by Martin Fowler (2019)

- The ML Test Score: A Rubric for ML Production Readiness and Technical Debt Reduction by Breck et al. (2017)

- Rules of Machine Learning: Best Practices for ML Engineering by Martin Zinkevich (2011)

General Work Stuff

- Out of Office: The Big Problem and Bigger Promise of Working from Home by Anne Helen Petersen and Charlie Warzel (2021)

- It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson (2018)

- Remote: Office Not Required by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson (2012)

“She’s beautiful, my dear, and beautiful people are always unpredictable. They know that whatever they do, they’ll be forgiven.” She picked another skirt off the floor. " Oh, yes," she sighed, “it’s even better than being rich, because beauty, my dear, never has a whiff of struggle or effort about it, but comes directly from God, and that’s enough to make it the only true human aristocracy, don’t you think?”

From Gianfranco Calligarich’s Last Summer in the CIty 📚

Photos aside, most of my posts to this blog are quotes from what I’m reading at the moment. Reading has always been a pretty big part of my life. In 2021 I continued a few trends in how and what I read; I also added a few new things that I expect to continue.

I continued to use the library extensively this year. I read (at least some of) 71 books for the first time this year, and all of them came from the library. There are a few caveats in that last sentence. I didn’t finish all of the 71 books, and so it isn’t fair to say I read them all… but I did at least start them. And from now on, I’m just going to say “read”, because I did finish most books and also I’m the boss of this retrospective. I also re-read some old favourites that I own, and I’m not including them in the list. All told, though, I think that’s a pretty healthy use of the library.

What I’ve found is that now I’ll hear about a book online or in a magazine and if it sounds interesting or useful I’ll put a hold on it as soon as I can. This has worked out pretty well. Sometimes I’m late to a hot book, and there are hundreds of people ahead of me; when it’s my turn I often have forgotten the context that prompted the hold, and getting the book is a nice surprise. Other times I’m early to a hot book (because I’m reading a review just before or soon after publication) and I have the pleasure of being pretty early in a long list of folks with the same idea.

This year 60% of the books I read were non-fiction. That feels like a lot to me. I generally prefer reading fiction, and think of myself primarily as a reader of fiction rather than anything else. But the numbers don’t lie! One reason this might be the case is that I think a greater share of what I read this year came from newsletter recommendations, and I think these skew non-fiction… but that’s conjecture on top of conjecture. I also think the fiction I read is “harder” than the non-fiction, so it might occupy a larger share of mind.

Here’s my a few of my top picks from the non-fiction I read this year:

- The idle parent by Tom Hodgkinson: being a little lazier as a parent is good for you and the kids. Have already gifted this a couple of times.

- To begin where I am : selected essays by Czesław Miłosz: a great introduction to Miłosz who, among other things, writes with a lot of style.

- It doesn’t have to be crazy at work by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson: Meet less, write more, chat less, focus more, check in less. An awesome guide to more humane work. Is it too much to give copies to the people I work most closely with?

- A philosophy of walking by Frédéric Gros. Make walking a part of your life. It is good for you and your mind, and many amazing people have relied on it.

- Storyworthy : engage, teach, persuade, and change your life through the power of storytelling by Matthew Dicks: tell better stories. I found the tone of this one kind of irritating in places, but it was too useful not to list.

And on the fiction side of things:

- The life of the mind by Christine Smallwood. I had something in my eye all the way through the back quarter of this book. Disorienting, often beautiful, in the end amazingly coherent.

- The buried giant by Kazuo Ishiguro: finally followed up on a recommendation from my wife, can’t believe I slept on this one for as long as I did. A beautiful, powerful novel wrestling with memory, collective trauma, enchantment and disenchantment and what love means over a lifetime. Also, a significant data point in support of my working theory that myth is returning as a means of sense-making (cf. The Green Knight, also Marvel/DC movies are not part of this theory and in fact are antithetical to it).

- The transit of Venus by Shirley Hazzard: a beautiful, stylish book. I had never heard of Hazzard before this year!

- Beautiful world, where are you by Sally Rooney: Rooney is counter-cultural and an excellent writer of dialogue. Counter-cultural in this novel: traditional sensibilities throughout, treatments of faith, and more. Not her best… but maybe the most interesting from an evolutionary perspective?

Enough about books; but let’s stick with print. I’ve been a long time subscriber to The New Yorker and Harper’s: I love getting both in the mail, love having copies lying around the house, love doing the crosswords with my wife over coffee, love being able to pack one in my bag every time I’m commuting. I don’t read everything in every issue, but I’d say I generally do read all the pieces I want to read (which is more than I can say for my “read later” bookmarks folder).

This year I’ve added print subscriptions to a few other periodicals: The Point, The Paris Review, The Hedgehog Review, and The London Review of Books. Honestly I think a big reason for this is that as a family we’re feeling a little more comfortable with discretionary spending within reason, especially around the home (“Are we not in saver mode anymore?” I remember my wife asking me earlier this year). Spending money on print publications feels a little selfish (I’m really the only person benefitting from them). But the quarterly journals in particular are such a pleasure to get and read: I really appreciate the attention to detail show in the curation, the artwork, and the typesetting.

Online, 2021 was the year of Substack. I now subscribe to 55 newsletters, very few of which are paid. Gradually it has become my primary time spent reading online, edging out my RSS feed (indeed, some of the newsletters I subscribe to used to be blogs or sites in my RSS).

Lots of ink has been shed on Substack this year, and I don’t really want to add to much to that. Here are two things I think are awesome about it. First, I like being able to follow the work of particular people over time. This isn’t all that new if they used to have a blog, but many didn’t. When I come across a piece in The New Yorker or Harper’s or elsewhere online that I like, usually I’ll look for other stuff that person wrote (If it’s a book, I’ll place a hold!). With Substack, I can subscribe and get everything new. If it turns out to be not that great, it is easy to unsubscribe!

Second, the clean formatting and lack of ads make for a much more pleasant reading experience than elsewhere online. I like how simple it is. I know some digital publications put a lot of work into making their features “native” online with fancy display elements and formatting… but generally I find that stuff to be useless at best and actively damaging at worst (very infrequently, say when the piece relies on data visualization, that rich formatting and content improves the piece and even becomes essential). A Substack newsletter is reliable, familiar, and doesn’t get in the way.

This has made it very easy, in fact, to move a lot of that reading offline. I’ve had a first generation reMarkable for a few years now and over the last year I’ve started reading a lot of my Substack content on it. The workflow is as follows: open the newsletter in a browser, click the Read on reMarkable bookmarklet, and then sync the device. The formatting is almost always perfect, especially if it’s a text heavy edition. I do this with almost everything relatively long, and it works super well.

Finally, something new over the last year was I started using Literal. I don’t actually use it that much, but I do enter the books I’ve read into the platform and occasionally poke around to see what other people are reading. I’m not sure if it’s worth recommending: if you don’t track books online then I don’t think it makes a strong argument yet that you need to, and if you already use something like Goodreads I don’t know if there’s much added value to justify the switching costs. But I thought I’d try it out and so far feel pretty good about it? I don’t know, if I dropped it tomorrow I don’t think I’d notice. But it does have a cool API to GraphQL so at some point, I think it would be great to play with access and then do some analysis on top of my reading data. That, for now, is enough to keep me onboard and willing to add my activity.

So that’s it! Lot’s of library reading, more print subscriptions, a ton of Substack, and then some useful tools IRL (reMarkable) and online (Literal). It’s been a year. On to 2022!

Let me make it clear from the start that I don’t blame anyone, I was dealt my cards and I played them. That’s all.

From the opening few lines of Gianfranco Calligarich’s Last summer in the city 📚

It is not surprising that we should believe that our fate is primarily ordained by outside agencies.

Yet we have all experienced times when, instead of being buffeted by anonymous forces, we do feel in control of our actions, masters of our own fate. On the rare occasions that it happens, we feel a sense of exhilaration, a deep sense of enjoyment that is long cherished and that becomes a landmark in memory for what life should be like.

This is what we mean by optimal experience. It is what the sailor holding a tight course feels when the wind whips through her hair, when the boat lunges through the waves like a colt-sails, hull, wind, and sea humming a harmony that vibrates in the sailor’s veins.

Contrary to what we usually believe, moments like these, the best moments in our lives, are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times —although such experiences can also be enjoyable, if we have worked hard to attain them. The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile. Optimal experience is thus some thing that we make happen.

The optimal state of inner experience happens when attention is invested in realistic goals, and when skills match the opportunities for action.

From Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi 📚

Honest conversation [with Dorothy’s dissertation supervisor Judith] was pointless, because a declaration of feeling (I hate you / I love you) could never account for the myriad complications that manifested as emotional, even spiritual conflict, but were rooted in something material and intractable – their positions in the game. Judith was a teacher and a foster mother and an employer, and more than that, she was a node in a large and impersonal system that had anointed her a winner and Dorothy a loser, and due to institutional and systemic factors that were bigger than either of them – not more complicated, no, because no system is more complicated than a single human being – no one of Dorothy’s generation would ever accrue the kind of power Judith had, and this was a good thing even as it was an unjust and shitty thing. Judith was old and Dorothy was young, Judith had benefits and Dorothy had debts. The idols had been false but they had served a function, and now they were all smashed and no one knew what they were working for. The problem wasn’t the fall of the old system, it was that the new system had not arisen. Dorothy was like a janitor in the temple who continued to sweep because she had nowhere else to be but who had lost her belief in the essential sanctity of the enterprise.

From Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind 📚

Dorothy looked out the window. I am leaving Las Vegas, she said to herself. That was a movie she had never seen. She thought of the book Learning from Las Vegas; she owned it, of course, but she had never read it. It was just another false start, another purchase toward the identity of a person she had turned out not to be.

From Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind 📚

For a long time [Dorothy] had loved karaoke. Honestly, she had loved it too much. The love was frantic but also complex, a complexity born of her desire to expose herself and be known, and her concomitant dread of exposing herself and being known. Of all the forms this conflict had ever taken in her life, karaoke was the purest.

From Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind 📚

The three of them represented the three potential paths of the graduate student: the one who wins, the one who leaves, and the one who does whatever it was Dorothy was doing.

From Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind 📚, a story about the academic precariat that, honestly, hits just a little too close to home.